The notion of "separation of church and state" is popular in our contemporary world. How this looks can vary dramatically from country to country. In the USA, there is a tension of keeping religion and state separate, but also fiercely defending religious liberty. In France, with their concept of laïcité1, the break is much more severe: the state is always favoured and personal beliefs are personal and should only be shared with like-minded people in private2. The principle of separation of church and state raises interesting questions when we shift our focus from religion to worldviews.

A worldview defines how one looks a life: its origins, purpose and destination. It cannot really be denied for someone, not objectively. Yet this is exactly what happens in a notion such as the separation of church and state. A government declares that people holding to certain worldviews (such as Christian theism) are not allowed to make decisions or judgements rooted in that worldview. Rather, they must make decisions based on a modernist-romantic-enlightened view; indeed, one which is also atheistic (or, at best, deistic) and naturalistic (these are the secular worldviews).

Apart from this oppressive, Orwellian Newspeak which state secularism mandates, there are other problems. We can ask from where the values that a secular state holds, comes (such as France's liberté, égalité, fraternité). The proponents of the secular state might argue that such values are self-evident3. Yet a closer inspection reveals something more sinister: they are values, because society and the state declares them to be. If one really interrogates these values in light of secular naturalistic ideas, one finds that one cannot ground them objectively. They might "work" to better society as a whole, but they cannot be grounded and, as such, are artificial. What is more, if, say, bettering society is not the ideal of state, then they can choose different values. And the assertion that a state should better a society is itself ungrounded in the absence of any higher power that gives mandates or exercises judgement. In the absence of such a power (in previous times held to be God), the state becomes this mandating power. Really, those in power, the victors, get to decide: whether dictators or peasant revolutionaries.

Yet another problem that secular states will and do face, is that its founding principles become outmoded. The USA and French Republic were founded in the modern era, whereas we are now in the postmodern (perhaps even transmodern) era, and people are no longer captivated by the romanticism which dominated that time period. People are now beginning to openly question the relevance of the constitution of the USA—written by affluent, white males over 250 years ago—in our contemporary world. The problem is that, if the values of a state are, effectively, arbitrarily decided (rather than being rooted in something objective, as one finds in, say, the Abrahamaic religions), then those values can rightly be challenged, and the noble idea of fraternity can begin to break down. Indeed, taken to its extreme, a constitution should be transient, rather than a permanent foundation. As the values of a society evolve, so should its legislative framework4.

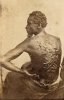

So a purely secular government has its problems: or, at the very least, some unpleasant implications. Yet even secular cultures in the West are not completely free from the influence of religion. Christianity has had a profound impact on Western culture, views and values. The legacy of Christianity goes far beyond a heritage of negative views on things like prostitution and homosexuality (as some people doubtlessly believe), but to fundamental notions such as justice, freedom and value. These notions would have looked very different in the West today if they had to develop without the influence of Christianity. As such, our modern secular values and laws—indeed, elements of our very thinking—are shaped by our Christian heritage. To deny it is to show ignorance of history.

How then should a government interact with it's citizens? Perhaps one of the most contentious areas is that of schooling. The state has taken over the education of children (previously done primarily by churches in the West). Many states mandate that a secular, naturalistic education be imparted on children. In other words, they wish to impress their worldview on children and are hostile towards parents who hold to different worldviews.

Worldview conflicts need not just involve religion. Consider a sincere solipsist named Andy. Andy does not believe that other minds exist. Instead, the "people" with whom Andy interacts every day are projections out of his consciousness and no more real than the characters from a dream. Any other conscious mind knows that Andy's worldview is false (because of their own conscious experiences), but are unable to convince Andy of this, because to him these objections do not come from other conscious minds, but merely come from his own mind who have assigned these projections certain kind of characteristics.

If Andy's neighbour, then, is only a projection from his own mind, there is nothing wrong with "murdering" "him". Of course, the state would object to this and take measures to prevent this. The arresting officer and prosecutor know that Andy's worldview is false; yet, ironically, they cannot know that they are not properly solipsist: whether they truly are the only consciences in existence or not. The might chose not to believe it, but they cannot know.

So we find that laïcité, just Christianity and solipsism, is a worldview (or, more properly, a product of a certain worldview). It is not an inclusive one and, really, is very narrow minded and exclusive. And it is no more grounded and legitimate than solipsism; neither can it be proven nor disproved. And this is why Christianity should be considered earnestly: it is the only falsifiable worldview. As discuss previously, if Jesus did not rise from the dead, then there is no Christianity. But if He did, then His claims should be taken seriously.

- 1. While the linked video lauds the virtues of laïcité for bringing harmony and religious tolerance, the first years after the French Revolution actually saw a state sponsored persecution of the Roman Catholic (in particular) church and active suppression of religious activities. Religious tolerance can also spring from religions themselves and is not dependant on secular values.

- 2. That said, France has a much more complicated history of having its politics dominated by the church, specifically the Roman Catholic church. One example is the infamous Cardinal Richelieu wielded great political power. Violent Roman Catholic suppression of the Reformation (particularly the Huguenots) also led to much bloodshed, and disillusionment with the church.

- 3. It has been discussed before that even a "self-evident" concept such as equality has divide people throughout the ages.

- 4. We should not kid ourselves into thinking that we can predict with any certainty what society's values will look like 50 or 100 years from now: whether it continues to develop in this way or that way, or whether it regresses or takes a completely different course.

- . Photo credit: Tilemahos Efthimiadis.

Latest comments