As this year draws to a close, I would like to reflect a little on the apostle Peter, and what we can learn from his example. I intend to do this by looking at a particular picture which I took during my second visit to Belgium this year.

Belgium has historically been a Roman Catholic country1. Within the Roman Catholic tradition, there is not greater authority on earth than that of St. Peter—and those who have inherited his office, which is the papacy. And so many churches in Belgium are named after St. Peter. The first which I encountered on my journey was in the city of Leuven. The building is impressive, as these old churches often are. Yet it was also disappointing. The origins of the current building lay in a rivalry with the city of Brussels, so the city of Leuven endeavoured to build a grander, more imposing church than the one in Brussels. This did not succeed as planned, as the funding eventually ran short. Today, like so many other churches in Europe, it functions more as a museum than a place of worship2.

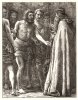

One of the artefacts which the church uses in its marketing to tourists, is a wooden carving of the head of Jesus, apparently originally from a crucifix dating from the 12th century. But what struck me more than anything else—any painting or carving or statue which I saw there—was a wooden statue of St. Peter against a wall: unadorned and unremarkable.

This statue left an impression on me. I could not quite explain it at first, but after months of thinking about it, I understand the significance that it had for me.

For all the reverence that the Roman Catholic church has for St. Peter, the New Testament describes a very real, very relatable human being. He is described as one of Jesus's inner circle (Mark 5:37), is the first of the disciples to recognise Jesus as the Messiah (Matthew 16:13–20), and becomes the "leader" of the apostles after Jesus's ascension into heaven. But, like the other disciples, he is also slow in understanding what Jesus means (e.g. Matthew 15:10–20), he could act rashly and violently (John 18:10–11), makes odd statements which betrays his lack of understanding (Luke 9:33) and is called out by St. Paul for a faltering faith (Galatians 2:11–14). He both had faith and lacked it (Matthew 14:22–33). But Peter's greatest shame was his denial of Jesus during His trial (Matthew 26:69–75, Mark 14:66–72, Luke 22:54–62, John 18:15–27), which came shortly after Peter's vehement promise that he is willing to die for Jesus (Matthew 26:31–35, Mark 14:29–31, Luke 22:33–34, John 13:36–38). Jesus calls him out on this and predicts Peter's denial. Peter may well have thought that he could "prove" himself to Jesus by resisting the temptation of cowardice and becoming a martyr of his beloved Friend and Lord.

But it was not meant to be, and Jesus's prediction was fulfilled. I do not think that we can judge Peter on this: can we really say that we would be braver and more loyal than he would have been? Could we say we would have been a closer and more devout friend to Jesus than Peter was? Our hindsight gives us the same foolish bravado which Peter had when he first said to Jesus that he was willing to die for him.

We cannot imagine Peter's relief and joy when he saw his Lord again—risen from the dead—and seemingly having forgiven their denial and cowardice a few days earlier. But at some point Jesus speaks to Peter and asks him—three times over—whether Peter loves him (more than the other disciples; John 21:7–19). At first Peter is eager to answer, but by the end the persistent questioning from Jesus must have felt like a chastisement for his denial of Jesus. But we see that Jesus's motive is not to chastise Peter, but rather to encourage him that he will, one day, finally have the appropriate opportunity and courage to die for his Master, granting him the desire which he previously had.

Finally, we come to the statue which so impressed me. When Peter recognised Jesus as the Messiah, Jesus gave him his commission:

Jesus answered him, "Blessed are you, Simon Bar Jonah, for flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father who is in heaven. I also tell you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my assembly, and the gates of Hades will not prevail against it. I will give to you the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven, and whatever you bind on earth will have been bound in heaven; and whatever you release on earth will have been released in heaven."

Matthew 16:17–19

What we have seen from Peter, is that he is a man with whom we can identify: not some superbeing, but rather a human character like us, with noble desires and deep flaws. He desperately desires to love and please his Lord. Yet he often comes up short and fails in his own expectations of who he should be.

And so it is to this unremarkable person to whom Jesus goes and says that he his blessed, and that he will have the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven, and all the awesome power and responsibility that comes with it. Peter was a fisherman by trade, not a learned scholar and theologian, so this cryptic charge would not have meant more to him than to us (who read with perfect hindsight).

What I see in the statue of Peter, is that of a man humbled by responsibility placed on him. He holds the keys to the Kingdom in his hands and he wonders, "Well, what now? What do I do with these? Where do I go?" Jesus told Peter to be the rock3 on which He would build His church, but Peter, in the statue, stands himself unevenly. This statue does not portray the resoluteness of other depictions of the noble Peter. Rather, it is of a man on whom it dawns that for him to succeed in him commission, his strength will need to come from outside of himself.

Nobody understands us better than Jesus, who has not only seen us since our births, but knew us from the beginning of creation already. He understands how frail we are even on our best of days. To have a relationship with Him does not mean to try and please Him through our efforts: rather it is to collaborate with Him and be empowered by Him and His Spirit. If we think that we can shun that collaboration, that is when we have already lost. This is true for all of us, even if we do not have a grand commission. Ours can be very ordinary and commonplace, but still have significance for Him. Whether we are commissioned to enter ministry or become a missionary; whether we are to enter a relationship or marriage; whether we raise children or have stewardship over goods or other people at work; whether we interact with other people for the briefest moments in time, we are to be in a submissive collaboration where we follow the lead of our Lord. Draw your strength from Scripture, prayer, meditation, fasting; never trust in your own strength and abilities.

But if you do succumb to pride, know that there is always forgiveness in repentance, which is turning back to our proper relationship with Jesus.

- 1. This was also a large contributing factor in the split between Belgium and the Netherlands, the latter being historically Reformed.

- 2. I was reminded of Friedrich Nietzche's story "The Madman", where the madman described the churches which he saw as "the tombs and sepulchres of a dead god". It certainly feels cold like a tomb (literally and figuratively) and almost devoid of a divine presence. Yet I saw one woman coming out of the confessional, sitting down and weeping—while the church as a structure felt empty, I knew that God was with that woman in her penitence, even in that place which seemingly has abandoned Him.

- 3. "Peter" is a Greek name which means "rock" and was given to him as a nickname by Jesus; his birth name was Simon.

Latest comments