For thousands of years, philosophers struggled with a particularly abstract, but very important, problem: how can we know what we know? This is called epistemology. Most of us probably don't think about this, but rather take it as obvious or self-evident. But spending a little bit of time on this question quickly reveals its significance. While there were sceptics before him, this kind of thinking led Descartes to a methodological scepticism until he reached a point where he felt that he could not know anything. Descartes resolved this problem for himself with his famous "I think, therefore I am", but even today people struggle with what they know, how they can know, and what they can know.

For example, there are philosophical thought experiments like the "brain in a vat" which exposes the frailty of our certainty. People who are solipsists—that is, people who don't believe that other minds exist, only their own—have a view of reality which, although it cannot be disproved, may well be considered a mental illness by others because of how radically it departs from how most people take reality to be.

Some people resolve this question for themselves by saying that only what their senses can perceive is real and knowable. This is call naturalism. While this sounds reasonable, closely examining this assumption will reveal that it fundamentally is not any more or less sound than what a solipsist believes. For example, do abstract numbers exist? Or, why are the mathematical axioms which we accept (which forms the basis of all mathematics, which in turn underwrites the mathematical sciences) actually correct?

If we further explore the implications of asking how we can know what we know, it leads to the question of God and how we can know anything about Him. As people started thinking more about naturalism and epistemological scepticism1, they began to conclude that we cannot know anything about God. This is known as deism, and for a time became popular among the intellectual elite. People still accepted that God existed, but He was unknowable. He is immaterial and in the realm of the spiritual, and we are material and in the realm of what is physical. Eventually, as pre-modernism turned into modernism, deism gave way to further scepticism and eventually widespread atheism.

But why is God unknowable? It is very much true that we cannot interrogate God: we cannot ask Him questions, or put Him under a microscope, or run tests on Him. Perhaps this is why deism gained popularity: as natural science advanced, people started to believe that something can only be known if it is testable. But there are some problems with this thinking. Not everything everyone believes is testable. For example, it cannot be proven that what our senses perceive is really real. If our senses deceive us consistently, and we can only gain information through our senses, then we are in trouble. This may sound silly, but this is a problem which epistemologists need to consider. Therefore, if we step into the philosophical realm of epistemology, our familiar set of tools turn out to be ineffective.

But, there is another way.

During His ministry on earth, Jesus said many things which baffled his audience, as well as his close disciples. This was partly intentional (Matthew 13:10–17). But another part is that what He was saying was not what His audience expected—or wanted—to hear.

Perhaps the prime example of His disciples getting it right, but also very wrong, is what happens in Matthew 16. Jesus asks His disciples who they think He is. Peter answers correctly: He is the Messiah, "the Son of the living God" (Matthew 16:15–16). This was a huge breakthrough: it was understood that the Saviour would be God Himself. But Jesus's praise for Peter (Matthew 16:17) did not last long.

From that time, Jesus began to show His disciples that He must go to Jerusalem and suffer many things from the elders, chief priests, and scribes, and be killed, and the third day be raised up. Peter took him aside, and began to rebuke him, saying, "Far be it from You, Lord! This will never be done to You." But He turned, and said to Peter, "Get behind Me, Satan! You are a stumbling block to Me, for you are not setting your mind on the things of God, but on the things of men."

Matthew 16:21–23

These are harsh words from Jesus to be said to one of His closest disciples. It seems like Peter is still struggling to understand the character—the identity—of Jesus: he can identify Jesus as the Son of God, but he won't accept Jesus's prophecy. Surely if Jesus was the Son of God, He would be correct in His prophecies? But it seems like Peter had another plan and purpose in mind for Jesus. At this time the Jewish people were expecting a warrior-king—like David—who would vanquish the enemies of Israel and bring peace and prosperity to the nation of Israel. Peter's thinking seems to have been stuck along these lines to some degree.

What this passage (Matthew 16:13–23) highlights is a tension seen throughout the Bible: what people want to believe about God verses who God said that He is.

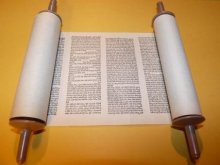

Christians believe in divine revelation. That is, that God revealed truths about Himself and the nature of reality and existence through human intermediaries. He did not reveal all things about Himself, but only what is necessary for us to achieve salvation through Jesus. Instead of knowing God through testing His qualities and characteristics, He reveals it about Himself; He speaks for Himself. He does this, precisely because there exists a gulf between the material and the immaterial, and the physical and the spiritual. What is more, in the person of Jesus, God actually breached this gulf.

Many people today dismiss divine revelation out-of-hand. They believe that it is either impossible for God to interact with people, or dismiss the recipients of the revelation as being mad, delusional, untrustworthy and/or deliberately lying. However, again, this kind of scepticism is no more, nor less, valid than any other grounding of knowledge. But hose who believe in divine revelation have an advantage over other ideas of how knowledge can be rooted: God is taken to know everything, including what cannot be known by humans. If He brings revelation, then people can have certainty over what can be known. Yes, it cannot be tested2, but, again, neither can it technically be proven that our sense perception accurately reflects an objectively real world.

In his song, Nothing 'bout Me, singer-songwriter Sting challenges the listener: "Run my name through your computer... check my records, check my facts; check if I paid my income tax; pour over everything in my CV, and you would still know nothing 'bout me". His intention is that all the data about him which can be studied may explain individual actions or paint a broad character outline, but it is not the same as knowing him personally. I don't know if Sting would say that someone could know him from speaking to his close family, his spouse, his former spouse and intimate friends, but I think he has in mind that if you want an inkling of knowing him truly, then you need to speak to him; that is, let him speak for himself; hear his perspective on his actions and character.

If we are willing to grant Sting that he is a complex being who can only be known by listening to what he says, do we not owe at least as much to God?

- 1. I am referring to the Enlightenment period, but the roots of this kind of thinking goes back to at least ancient Greek philosophy.

- 2. This is not actually true, according to God. In Deuteronomy 18:22, He says that true prophets can be distinguished from false prophets in whether the prophecies come true.

Latest comments